What is ‘Stage 0’ breast cancer and how is it treated?

Extreme Climate Survey

Scientific news is collecting questions from readers about how to navigate our planet’s changing climate.

What do you want to know about extreme heat and how it can lead to extreme weather events?

What is stage 0 cancer?

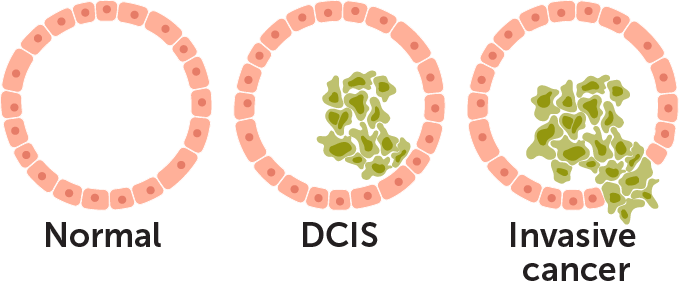

Stage 0 cancer is a condition where the cells in the body look like cancer cells under a microscope, but have not left their original location. It is also known as carcinoma in situ or noninvasive cancer because it has not invaded any of the surrounding tissue. Sometimes it is not called cancer at all.

“A lot of people think of these as some kind of precancerous lesions,” says Julie Nangia, an oncologist at Baylor College of Medicine in Houston.

There are many different types of Stage 0 cancer, depending on which tissue or organ the cells are in. Some cancers, such as sarcomas (bone or skin cancers), do not have a stage 0.

Fishel’s diagnosis is called ductal carcinoma in situ, or DCIS. This means that some cells in the milk ducts in the breast look abnormal, but those cells have not grown out of the milk ducts and moved into the rest of the breast tissue.

The problem is that they can. If abnormal cells break through the milk duct, the severity of the cancer that follows can range from Stage 1 to the more advanced Stage 4, depending on the size of the tumor and the extent to which the cancer has spread throughout the body.

How common is DCIS?

Before regular screening mammograms became the norm, DCIS accounted for only 5 percent of breast cancer diagnoses, says breast cancer surgeon Sara Javid of the Fred Hutch Cancer Center in Seattle. (SN: 6/13/14).

Now, DCIS accounts for about 20 percent of newly diagnosed breast cancers. About 50,000 cases are diagnosed in the United States each year, and it appears in one out of every 1,300 mammograms.

Still, because Stage 0 breast cancer doesn’t really have any symptoms, it’s possible to have it and never notice it. “Many women have DCIS and don’t know it, especially older women, since it’s usually a disease of aging,” says Nangia.

For other Stage 0 cancers, the situation is different. Stage 0 cancer in other internal organs is often too small to show up on a scan. Widespread screening tests in other organs may be unreliable or require too many resources to perform in an entire population.

The main exception is melanoma in situ, or stage 0 skin cancer, which can be visible on the skin. This diagnosis is even more common than DCIS: Nearly 100,000 cases are expected in the United States in 2024.

How do you know if you have DCIS?

Most cases of DCIS are caught by regular screening mammograms, the kind that people with breasts are encouraged to get every year starting at age 40 or 45. That’s how Fishel got her DCIS diagnosis.

“This is exactly why we want women to have screening mammograms,” says Nangia. “We want to catch cancer in its earliest stages, where it’s incredibly easy to cure.”

How is DCIS treated?

Most DCIS is treated with surgery, radiation, or some combination of the two. Chemotherapy is never recommended.

The surgery may be a “lumpectomy,” a localized operation that simply removes lumps that look like cancer. If there are multiple cases of DCIS in the same breast, a total mastectomy may make sense. After that, some patients receive radiation to further eradicate the cancer cells, and some receive hormone therapy to reduce the chances of it coming back.

“The goals of therapy are really twofold,” says Javid. First, the therapy can prevent DCIS from evolving into invasive cancer. But also, the treatment can rule out other invasive cancer that was lurking next to the DCIS but was missed by a biopsy. There’s a 5 to 20 percent chance that a pathologist examining tissue removed during surgery will find invasive cancer already there, Javid says.

Chances of survival are good: People with Stage 0 breast cancer have a normal life expectancy with a survival rate of about 98 percent after a decade of follow-up.

Is surgery always the best treatment?

This is controversial. It is not clear whether the long lifespan is because the test catches abnormal cells before they become invasive, or if those abnormal cells would not have invaded other tissues at all.

“What we know now is that probably not all cases of DCIS have the ability to progress to invasive cancer, and even those that do may not progress to invasive cancer during a patient’s lifetime,” said surgical oncologist Shelley Hwang. of Duke University School of Medicine at. Durham, NC, in a video explaining her research.

“As screening technology improves, we are able to detect early and early conditions that may look like cancer but may not necessarily behave like cancer,” Hwang said. “What this means is that for the majority of women who are diagnosed and treated for DCIS … these treatments may not be of much benefit to the patient.”

Are there any other options?

The main alternative to surgery is called active surveillance or watchful waiting—basically, you keep an eye on the cells and wait to see if they do anything scary.

This may be a familiar concept to anyone who has been diagnosed with slow-growing prostate cancer. It used to be that every diagnosis of prostate cancer came with a recommendation for surgery and radiation treatment. But clinical trials showed that patients who monitored their cancer and put off surgery until it turned malignant had life expectancies similar to those who had their cancer cells cut out.

For DCIS, there are ongoing clinical trials in the United Kingdom, Europe, the United States and Japan to see whether active surveillance has better or worse outcomes than surgery. At least one of those trials, the COMET study in the United States, is expected to publish results by the end of 2024, says social scientist Thomas Lynch of Duke University Medical Center.

“The results may increase treatment options for women diagnosed with low-risk DCIS if active monitoring is shown to be a safe and effective alternative to surgery,” he says.

But without a way to tell which cases of DCIS will become dangerous, doctors generally recommend treating all cases as if they do.

“I also don’t think you can underestimate the psychological effects of just leaving a breast cancer out there and looking at it,” Nangia says. “It causes patients a lot of anxiety. . . . There’s definitely a mental component to all of this.”

Is there any way to tell which of these abnormal cells will become invasive cancer?

Alas, no – at least not yet.

Doctors have a grading system for classifying which cells they think are at the highest risk of becoming invasive. A low grade is less likely, a high grade is more likely. Fishel was diagnosed with high-grade DCIS that has begun to spread into adjacent tissue, suggesting surgery is a good fit.

But many research groups around the world are trying to become more precise. They are looking for features of Stage 0 cells or their environments that will carefully separate preinvasive from dormant cases (SN: 9/27/13).

A 2022 study looked at how calcium phosphate minerals form within the ducts with DCIS, with the goal of eventually linking these details to disease progression. Some studies are searching the genome of cancer cells for signs of danger. Others look at the molecular properties of the cells themselves, or their microenvironments in the body.

Do announcements from celebrities like Danielle Fishel help?

“Oh, absolutely, it’s so helpful,” says Nangia. “Especially when they do it in a thoughtful way,” as Fishel did.

Nangia also points to Angelina Jolie, whose discovery in 2015 of her family’s cancer history and her decision to have preventative surgery sparked a national discussion about how genetics can affect cancer risk. (SN: 4/10/15).

Beyond raising awareness, celebrity endorsements can encourage people who may have been on the fence to get screened.

“I think what we’re going to see now is some women who haven’t had their screening mammograms say, ‘Oh, I should do that too,'” Nangia says. “I hope we see a wave of more people coming in for preventative care.”

#Stage #breast #cancer #treated

Image Source : www.sciencenews.org